(This corrects one paragraph in the story, involving the circumstances of the arrest. The only change is to the paragraph that begins: “He was on probation”)

Some stories leap quickly from real life to the TV or movie screen.

Then there’s “Free Chol Soo Lee,” the involving documentary that debuts at 10 p.m. Monday on PBS’ “Independent Lens.” It percolated in Julie Ha’s mind for somewhere close to four decades.

That started with Korean-American reporter K.W. Lee, she told the Television Critics Association. “I was 18 years old and he inspired me to want to become a journalist.”

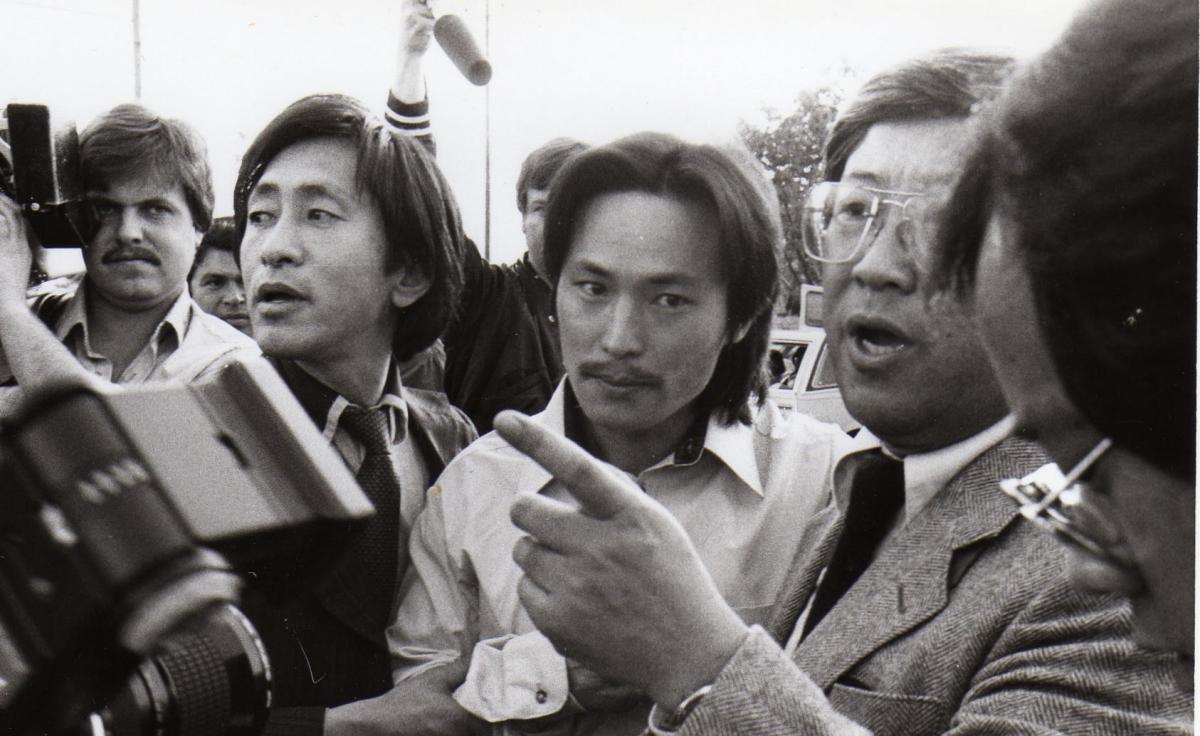

His stories helped spark a retrial. In 1983, after a decade in prison, Chol Soo Lee (shown here, center) was free.

Much later, in 2014, Ha went to the ex-prisoner’s funeral. “K.W, Lee stood up,” she said, “and he was clutching this Buddhist monk’s walking stick that Chol Soo had carved for him out of a tree. And he said, ‘Why is this story underground after all these years?’”

Ha decided to bring it above-ground. After a career in print – including as editor-in-chief of the national Korean-American magazine – she made her first film. She and Eugene Yi, a veteran movie editor, spent years working on it, going through Chol Soo Lee’s prodigious letter-writing and talking to people who recall him vividly.

“This was truly the first time that Korean-Americans got together,” Gail Whang, an educator who was on his defense committee, told the TCA.

He was a likable person, said Ranko Yamada, a Japanese-American lawyer who was his friend. “I had heard that even as a child, he was very social, friendly and generous. He would give all his stuff away. And he had very little …. As an adult, he was always such a considerate and caring person.”

But circumstances were brutal. His mother had married an American soldier and moved to the U.S., returning to retrieve her son when he was 12. He had trouble with the language and school, spending much of his teen years in juvenile detention, foster care and mental institutions.

He was on probation when, at 20, witnesses picked out his old mug shot and said he was the man who had fled a murder scene in San Francisco’s Chinatown. None of the witnesses were Asians; later studies have shown that witnesses are unreliable when identifying other ethnic groups.

Lee was convicted, but protesters persisted. They pointed to police failure to follow (or provide to the defense) leads that contradicted his guilt.

In prison, Lee was a strong and compassionate letter-writer. Out of prison and needing money, he floundered. “It’s the skill set that you have been raised with,” Yamada said. “He had very little.”

Officials kept insisting that Lee was guilty. But Ha said she got a surprise one day, when she cold-called Frank Falzon, the former police detective who worked the case:

“He said, ‘This is one case in my over 20 years as a homicide detective, where I wonder, you know, when I meet my maker, I want to know: Did he do it or not?’”

A passionate story percolated for decades

Some stories leap quickly from real life to the TV or movie screen.

Then there’s “Free Chol Soo Lee,” the involving documentary that debuts at 10 p.m. Monday on PBS’ “Independent Lens.” It percolated in Julie Ha’s mind for somewhere close to four decades.

That started with Korean-American reporter K.W. Lee, she told the Television Critics Association. “I was 18 years old and he inspired me to want to become a journalist.”

His stories helped spark a retrial. In 1983, after a decade in prison, Chol Soo Lee (shown here, center) was free.

Much later, in 2014, Ha went to the ex-prisoner’s funeral. “K.W, Lee stood up,” she said, “and he was clutching this Buddhist monk’s walking stick that Chol Soo had carved for him out of a tree. And he said, ‘Why is this story underground after all these years?’” Read more…