Chances are, this isn’t what a kid in rural Louisiana expects:

Some day, his youth will be turned into … an opera. A real one, opening the Metropolitan Opera season, with bejeweled fans applauding and bespectacled critics praising.

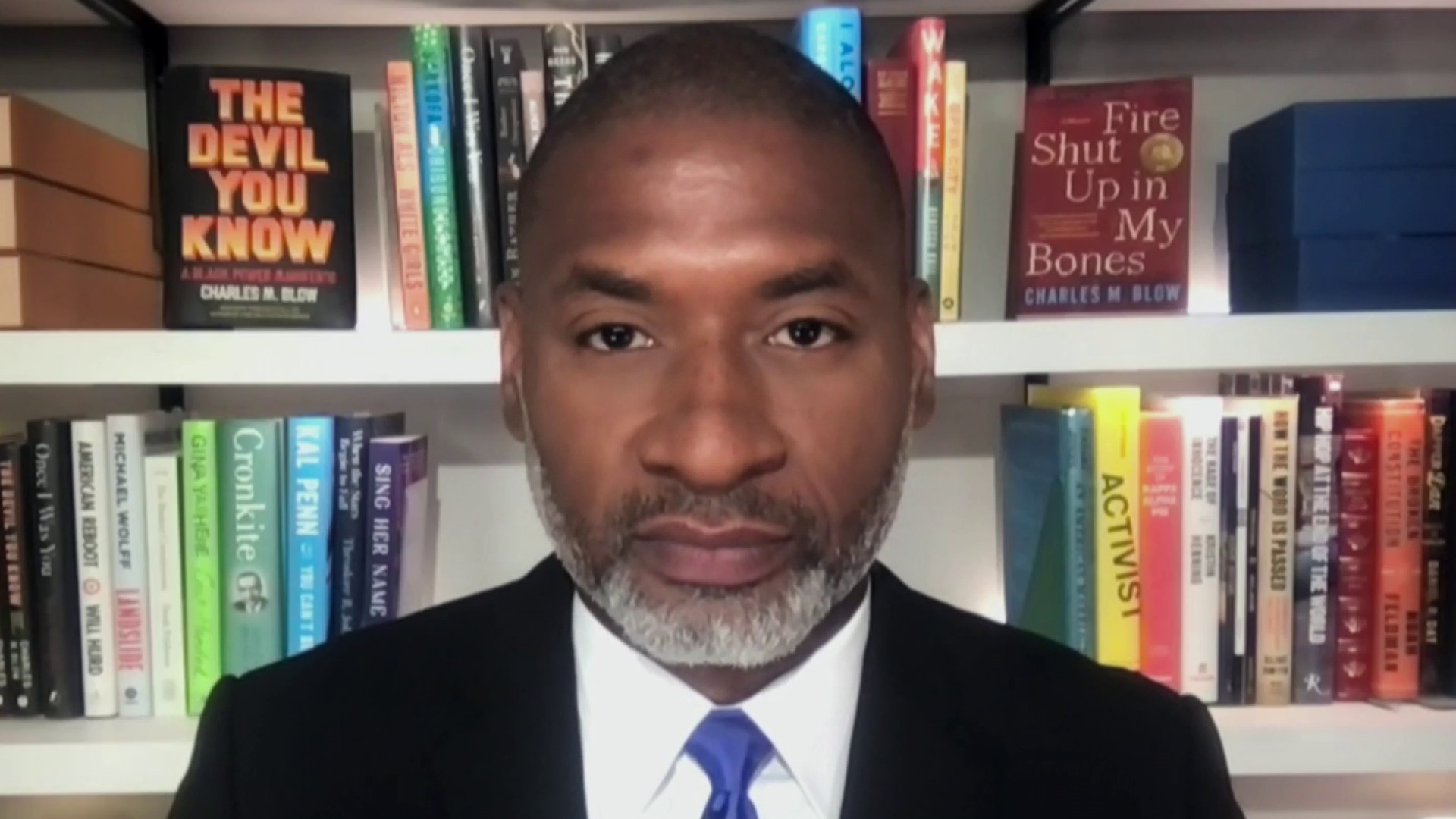

That’s what happened to Charles Blow (shown here). His memoir — “Fire Shut Up in My Bones,” at 9 p.m. Friday (April 1) on PBS – was the first show after the Met’s long Covid break.

“We were determined, with our return, to pack our schedule with more new works and more experiences that (are) relevant to a modern audience,” said Peter Gelb, the Met’s general manager.C

That’s what PBS viewers will catch Friday. The first Met show with a Black composer (jazz great Terence Blanchard) and Black librettist (actress-turned-author Kasi Lemmons), “Fire” ripples with passion.

It also reflects a social quirk: Birth-order can be crucial. A first-born might be strong and decisive (or just bossy) … a last-born might be beloved and coddled (or just bullied) … a middle-born might be ignored.

“I am the youngest of five boys,” Blow said, in a virtual press conference with the Television Critics Association. There are privileges to being “the baby boy – and there are negatives.”

When his parents separated, he was 5 – “not quite old enough to venture off and ride bikes with my brothers, all over town. (I) learned to kind of play alone.”

Long-term, that may have helped mold an exceptional soul. In high school, he was valedictorian and started the school newspaper. In college (Grambling), he edited the newspaper, started a student magazine and was president of Kappa Alpha Psi. His career took him to the New York Times, where he was the graphics director and is now a columnist.

But short-term, there were deep problems. His mother had to race between jobs, often leaving him by himself. “There’s an incredible loneliness that was baked into that …. Loneliness and isolation – predators look for that. They look for someone who’s been separated from the herd.”

Blow’s memoir tells of sexual abuse … and of his lust for revenge. It drew praise – and a visit from Blanchard and Lemmons. “I couldn’t figure out how they were going to do that – turn it into an opera.”

First, Lemmons gathered more details. “Wherever Charles walked,” Blanchard said, “Kasi was two steps behind him with a pad and pencil.”

She spent a year on the libretto. Then it was Blanchard’s turn.

“My father loved the opera,” he said. “While I was a kid, he would play opera in the house all the time. He was an amateur baritone …. They heard me sing and realized that wasn’t going to work.”

So he took piano lessons until – shortly after his dad had bought a piano for him – he heard a trumpeter. Blanchard became a master player (18 Grammy nominations and five wins) and composer, with two Oscar nominations and two operas – the second one soaring to the Met and PBS.