For four centuries, mobility has been crucial to Blacks in America.

At first, a PBS documentary points out, it was banned. Many slaves never traveled more than a mile.

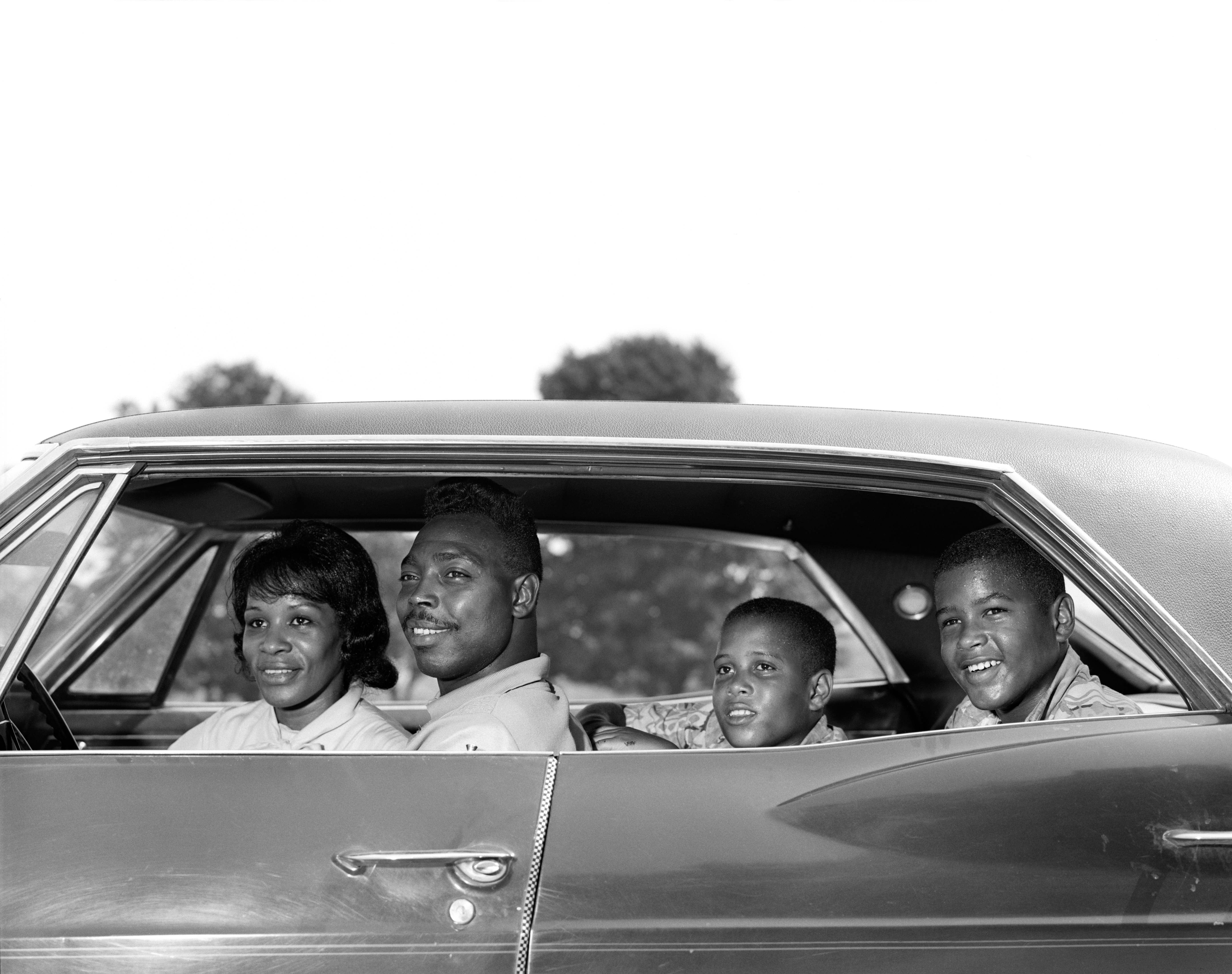

Much later, travel was joyous (shown here) … or perilous. The film takes us through the “Green Book” era of discrimination … and on to the fears that go with a modern traffic stop.

That leads to its title: “Driving While Black: Race, Space and Mobility in America” airs from 9-11 p.m. Tuesday (Oct. 13) on PBS.

The title may give the impression that the entire film is about traffic-stop crises. Only the last part is … and several portions of that are borrowed from a terrific report done by ABC a dozen years ago.

Beyond that, the film offers much more. Gretchen Sorin – a historian who wrote a similarly titled book – and master documentarian Ric Burns combined for an exhaustive portrait of Blacks’ joys and fears involving transportation,

For a century after the Civil War, mobility was limited. The South had its back-of-the-bus rules and car ownership was limited. It took a huge effort to maintain the 1955 bus boycott in Montgomery, Ala.

And for Blacks who had cars? The most optimistic view is the one the film quotes from Mark Twain: “Travel is fatal to prejudice, bigotry and narrow-mindedness.”

Often, however, bigotry prevailed. Restaurants, hotels and gas stations turned Blacks away.

One solution was created by Victor Hugo Green, a Harlem mailman. In 1936, he researched and wrote “The Negro Motorists’ Green Book,” listing amenable businesses.

There were other such books, the film says, but Green’s (printing 15,000 copies a year) was the leader. The places it listed, one persons says, offer “a testimony to black entrepreneurs.”

Some were homemade operations, places where the traveler could get a bed, a meal and some local guidance. Others were large-scale. The film briefly views classic resorts, from Oak Bluffs on Martha’s Vineyard to lakeside Idlewild in Michigan. In New Orleans, it discusses the classic Marsalis Motel and the Dooky Chase Restaurant.

“I fed everyone – James Baldwin, Thurgood Marshall,” Leah Chase says in the film. That’s a fraction of a list that includes Martin Luther King, Barack Obama, George W. Bush, Quincy Jones, Ray Charles, Lena Horne, Henry Aaron and more.

The Green Book businesses offer a grand history, but many were cut short by two factors.

In 1956, the Interstate Highway System began. At the least, highways diverted travelers from the turf of mom-and-pop businesses; at the worst, they plowed through Black neighborhoods.

And in ‘64, the Civil Rights Act was passed. The final Green Book was published two years later.

In the first edition, Green had written: “There will be some time in the near future when this guide will not have to be published. That is when we as a race will have equal rights.”

It was not the near future; the guide continued for 30 years … and the debate over equality lingers. The PBS film closes with stark reminders – some from the ABC film, some from recent camera-phone footage — of traffic stops that turned violent.

And the businesses that once nurtured Black travel? Less that three percent of those in the Green Book still exist, the film says. Still, their impact lingers.

The Marsalis Motel was razed in 1993. It’s owner died in 2004 (at 96), but his love of music and New Orleans continued via his son (Ellis Jr., who died of COVID this year at 85) and grandsons (Wynton, Branford and Delfeayo).

The Dooky Chase restaurant was flooded by Hurricane Katrina, but re-opened two years later. Leah Chase continued as chef, until shortly before her death last year at 96. Her restaurant survives, as a bridge between generations of American travel.